By Fredrick KunkleJuly 31, 2022 at 6:00 a.m. EDT

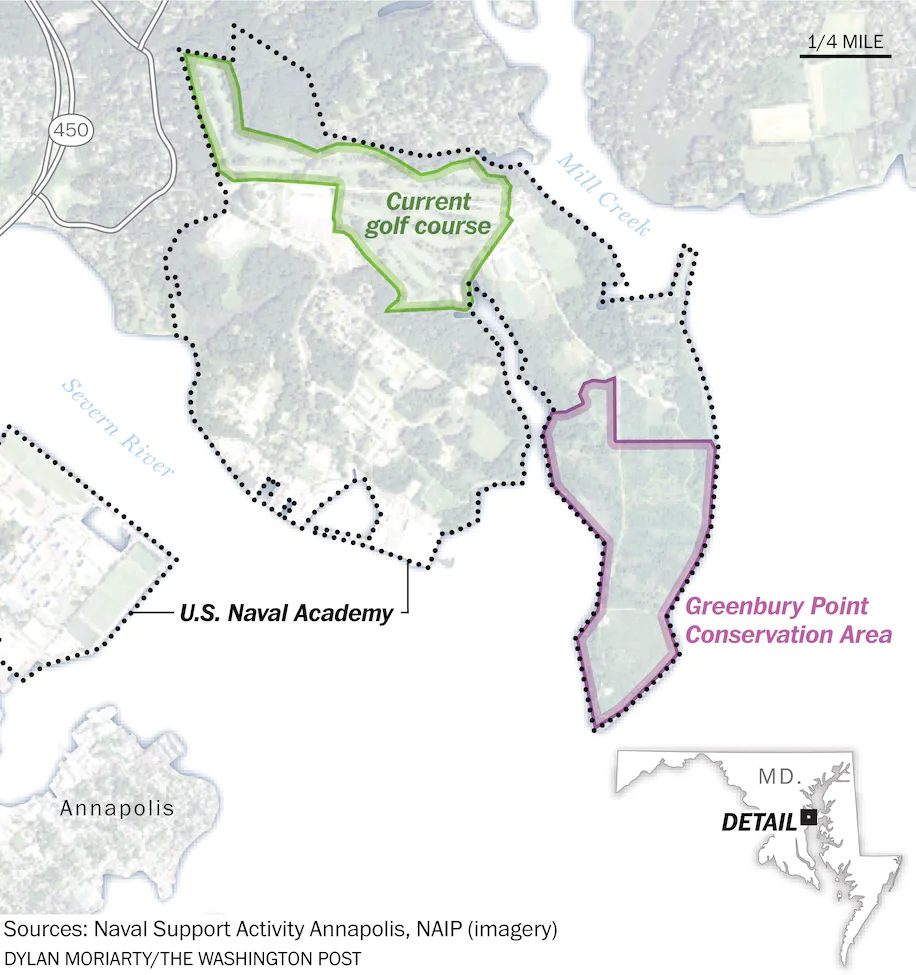

When the U.S. Naval Academy’s athletic director wrote to the secretary of the Navy earlier this year proposing to build a new golf course on Greenbury Point across from the military school in Annapolis, he said he only wanted to float the idea for further study.

Instead, Chet Gladchuk’s pitch became a call to arms.

Soon after the proposal became known this spring, hikers, birders and environmentalists launched an impassioned campaign to preserve the Greenbury Point Conservation Area overlooking the Severn River and Chesapeake Bay. The green patch of land is visible from the city, and its three radio towers — remnants of an array that once communicated with Navy submarines in the Atlantic Ocean — have become landmarks for sailors clearing the Chesapeake Bay Bridge.

Opponents fear that an additional 18-hole golf course on the peninsula will destroy important wetlands and forest habitat, pollute the bay and cut off the public’s access to the shore. They also worry that the proposal is further along than the Navy will admit and that well-connected Navy veterans and wealthy graduateswill have outsize influence in determining whether it gets built.ADVERTISING

“There’s lots of people here that are loving and using this place: elderly folks, kids being pulled in little wagons . . . people walking dogs, people training for marathons . . . people fishing,” said Joel Dunn, president and chief executive of the Chesapeake Conservancy. “This is a very special resource for the community, and we’re very grateful for the Navy for letting us use it, visit it, enjoy it. So the threat of taking it away with a private golf course is really disconcerting to all of us here.”

Eastern Shore development sparks fight

Twenty-five environmental organizations — including the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, the Severn Riverkeeper and the Maryland League of Conservation Voters — wrote a letter in Mayto Navy Secretary Carlos Del Toro urging him to kill the plan. A poll commissioned by the Severn River Association and the Chesapeake Conservancy found more than two-thirds opposed the idea.

A Facebook page called Save Greenbury Point has attracted about 2,000 members, and more than 4,700 people have signed a Change.org petition. Letters have gone out to members of Maryland’s congressional delegation asking them to intervene.

Though several opponents said they have long respected the Navy’s efforts to balance its mission with protecting the bay, they criticized the proposal and what they said has been a lack of transparency.

“This is a developer’s typical MO,” said Jesse Iliff, executive director of the Severn River Association. “Hide the ball until you’re in the end zone and then spike it.”

Gladchuk, though unsurprised by the outcry, characterized the response as alarmist and wildly premature to what he describes as the equivalent ofa trial balloon.

“There’s no bulldozers, there’s no plan, there’s no architectural design — there’s no architect,” Gladchuk said in an interview. “We looked at Greenbury Point and said, ‘Gee, wouldn’t it be interesting to study the feasibility of creating a magnificent recreational facility on the point?’ ”

In his Feb. 15 letter, Gladchuk — who is president of the Naval Academy Golf Association (NAGA) as well as the academy’s athletic director — urged Del Toro to back the project. He saida second golf course — which the NAGA would develop on property to be leased from the Navy — would fit in well with the newly renovated and redesigned golf course. The overhaul, which began in 2020 andcost close to $10 million, also includes plans for a new clubhouse with a dining area.

“I am asking for your support,” Gladchuk says in the letter, a copy of which was obtained by The Washington Post. “I look forward to visiting with you to show you our conceptual plans for the course.”

But there has been no meeting and, as yet, not even a map of a new golf course, Gladchuk said. In his imagining, though, about 280 acres of the Greenbury Point Conservation Area and adjacent land would be developed into an 18-hole golf course set among nature trails, a boat launch, birdwatching blinds, physical fitness sites and other features. Areas with tainted soil from previous Navy activity would be cleaned up, and sea walls raised in anticipation of higher sea levels because of climate change.

“It’s overgrown,” Gladchuk said of the area now. “It’s infested with ticks. The walking trails are full of invasive species. It’s just undeveloped land.”

Hundreds, if not thousands, of golfers use the existing, privately funded course, including midshipmen in varsity, intramural and physical education programs; active military personnel from all branches, including civilian employees; and veterans and academy graduates, Gladchuk said. Members of the public are welcome to play for a fee or become members.

Even if the Navy were to give the all-clear to proceed with a new course, he said, the process would require multiple levels of bureaucratic review, environmental and historical studies in line with federal law, as well as ample public comment. It also would have to take into account a binding, decades-long agreement by the Environmental Protection Agency and state governments located in the watershed to restore the bay.

“It would take years to develop,” Gladchuk said.

He also estimates the NAGA would need to raise at least $35 million to make it happen.

In the meantime, his proposal is moving up the chain of command, beginning with Naval Support Activity Annapolis, an installation that’s part of Naval District Washington and serves the academy, Greenbury Point and nearby Navy properties. Ed Zeigler, a spokesman for Naval District Washington, said nothing has changed since Gladchuk’s letter and referred further questions to the Navy’s FAQ page.

Jennifer Crews-Carey, a retired Annapolis police officer who has helped organize opposition to a new golf course, said opponents keep pushing the Navy to learn more about the proposal’s status.

“I doubt it’s on a napkin,” said Crews-Carey, 56, of Cape St. Claire.

Under the tax code, the Naval Academy Golf Association is a nonprofit social club created to promote and support golfing and operate the academy’s existing golf course.

The NAGA had revenue of more than $2.5 million from greens fees, initiation fees and golf cart rentals, and membership dues of more than $1.6 million in 2018, according to the most recent public financial statement. The statement estimates the value of the property at nearly $5.8 million.

There are 510 dues-paying members, split evenly between military and civilian, with another 118 on a waiting list, Gladchuk said. The initiation fee — $22,500 for a family membership — is steeply reduced for military members, who pay $5,500. Greens fees are similarly discounted.

Besides the golf course, the Navy’s property across the Severn River from the academy supports several uses, and it has rugby fields and a rifle and pistol range. Much of the 827 acres was purchased in 1909 by the Navy as farmland to support the academy’s dining hall.

Beginning in 1918, Greenbury Point was a radio research and transmission site until satellite communications rendered it obsolete. The radio towers were decommissioned, and all but three were razed.

Since 1999, Greenbury Point has been managed as a conservation area. During a recent tour, the Chesapeake Conservancy’s Dunn and a group of preservationists pointed out the rich diversity of wildlife there — although part of the conservation area was off limits while the shooting range was in use.

Butterflies floated over stalks of milkweed, and an indigo bunting piped from a treetop at the edge of a ragged field. Hundreds of creatures, including ospreys, deer, tree frogs, turtles and, yes, ticks, make their home on the site, whose nearby waters support oysters and other marine life.

The land was inhabited by humans as early as 10,000 years ago and settled by Europeans as far back as 1649, said Sue Steinbrook, an organizer of the opposition who is also researching a history of the area.

“It’s a rare, rare resource for people to use,” Dunn said. “We all care about the Severn River and the Chesapeake Bay, we want people to invest in its future, and we’re devoting billions of dollars to restoring it. But if you don’t get to see it, and you don’t get to enjoy it, you’re not going to vote for it.”0 CommentsGift Article

By Fredrick KunkleFredrick Kunkle is a reporter on the Metro desk. He has written about transportation, politics, courts, police, and local government in Maryland and Virginia. Twitter